And Wilhelm Reich on the Wurlitzer

According to Sarah Chait, there are three types of visitors to the Wilhelm Reich Museum in Rangeley, a resort town in the mountains of western Maine. First, the people who come to the area to fish but get rained out and need something else to do. They tend to laugh at the word “orgasm,” spend a long time taking in the books in controversial Austrian-born psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich’s extensive time-capsule-like library, and sometimes lean in and ask the guides, “Do you really believe in all of this?” Then there’s the “Reichians making their little pilgrimage.” One such visitor broke down in tears while purchasing her ticket. She’d wanted to come to Orgonon—the 175-acre estate where Reich built cabins, a laboratory, and an observatory—since the 1970s. Finally, there are the new-age people (crystals, anti-5G) who rave about “orgone energy” without understanding that Reich took himself seriously as a 20th-century scientist.

“Reich didn’t want to be admired esoterically. He would have hated that,” says Sarah, the twenty-four-year-old printmaker and papermaker who served as Orgonon’s first resident-intern.

I met Sarah at the 2023 installment of the annual Reich conference.1 Held in the gymnasium of the Rangeley Lakes Regional School, “Getting to the Core: Wilhelm Reich’s Therapeutic Principles” attracted psychoanalysts, therapists, board members, and Reich fans from around the world. Sarah, wearing a “Brian Jones Lives” t-shirt, made sure each participant received the blue vinyl folder containing the week’s schedule and nametag she’d compiled for each of them.

Sarah spent much of the week schlepping conference supplies from Orgonon and the local IGA near the scenic lookout to the freshly waxed floors of the school gym. She helped Orgonon’s executive director, David Silver set up the bilingual sound system, arrange breakfast, and make coffee. The 75 participants, attending both in-person and via Zoom, ranged in age from 12 (the daughter of an attendee) to 82 (moderator Philip Bennett).

David, 62, stood behind a table near the bleachers containing several computer screens and a mixing board. “I feel like I’m working at a NASA mission control center,” he said, as he muted and unmuted virtual participants, monitored the chats, switched out microphones, and checked sound levels in the gymnasium and beyond.

Participants wore headphones and sat in green plastic chairs with an optional piece of foam to make sitting for the full week a more comfortable experience. This accommodation was important to board president Renata Reich Moise, a sixty-three-year-old recently retired midwife and painter who is also Wilhelm Reich’s granddaughter.2 The merch table by the door of the gymnasium door was full of Reich-inspired mugs and t-shirts, as well as Reich’s books. Seeing those volumes displayed so openly felt almost miraculous, knowing that in 1956 and 1960 they would have been seized and incinerated by the US government. Some refer to this as the only federally-sanctioned book burnings on US soil–to date, however, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considered the books as labeling for fraudulent medical devices rather than literature. Regardless, Reich is one of the few authors whose books were burned by the Nazis and the US federal government. The Nazis were most opposed to The Mass Psychology of Fascism and The Sexual Struggle of Youth whereas the FDA set flame to any books or materials that discussed Reich’s concept of orgone energy3—burning several tons of his literature in a New York City garbage incinerator.

While neither Reich nor all Reich enthusiasts or scholars may agree with me on this, Reich’s work can be thought of in two distinct but connected eras—the psycho-social-political and body-psychotherapy contributions of the 1920-30s in Europe (character analysis, muscular armoring, his synthesis of Marxism and psychoanalysis, bio-energetics), and everything that came after (orgone energy investigations, the invention of devices such as orgone accumulators and cloudbusters, the flying saucers).

As David puts it, “If Reich had died in a plane crash in the 1940s, he’d be as well-known as Freud, without any of the controversies.”

Instead, Reich died at the Federal Penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1957, shortly before he was up for parole. He was sixty years old and in the midst of serving a two-year sentence for being in contempt of an injunction—the FDA declared that orgone energy does not exist and that Reich was defrauding consumers through his books and orgone energy accumulators. When the FDA initially asked for an injunction, Reich wrote to the judge, explaining that he would not appear in court, as a court of law could not judge basic scientific matters.

A Decree of Injunction was issued, nevertheless, ordering orgone energy accumulators and their parts to be destroyed as well as all materials containing instructions for the use of the accumulator. In addition, the injunction banned a list of Reich’s books containing statements about orgone energy until all references to orgone energy were removed. The injunction also prohibited the shipment of orgone energy accumulators across state lines. This is ultimately what led to Reich’s imprisonment. An associate of Reich’s transported a truckload of accumulators and books from Rangeley to New York City, unbeknownst to Reich.

After he was found in contempt, Reich chose to represent himself in court. As Ilse Ollendorrf Reich, his second wife, notes in Wilhelm Reich: A Personal Biography, “In all of these hearings and motions Reich acted and signed as Counsel for the Defense EPPO (Emotional Plague Protection Office)…”4

Contrary to popular belief, Reich never claimed that orgone energy accumulators would cure anyone’s cancer and was very transparent about the results of his research. Yet following the publishing of The Strange Case of Wilhelm Reich in 1947, an article in The New Republic by Mildred Edie Brady that the Reich Museum states was “filled with distortions and innuendos about Reich’s sexual theories and orgone research” the FDA began its expensive, 10-year investigation of Reich.

Before the conference, I told a friend who considers himself familiar with Reich—at least in the pop-culture sense—that I was going. “Oh, you’re going to meet so many weirdos,” he said, excited for me.

I would have to disappoint him. The Wilhelm Reich Infant Trust board members, the accredited, practicing psychoanalysts and therapists, and even the hardcore Reich enthusiasts were not that weird.

Mornings were spent in the gym with in-person and virtual presentations such as “Bioenergetic Pulsation,” “Character Defenses and Muscular Armor,” “The Centrality of the Function of the Orgasm in Dr. Reich’s Clinical Model,” and “Emotional and Social First Aid for Children.” Afternoon sessions were not broadcast or recorded, allowing for in-person attendees to have an even deeper connection to the work presented and to each other.

Over the course of the three days I spent at the week-long conference, I watched Renata stride across the gym with therapist Will Freeman, during an experiential movement session called “Being Present in Heart and Mind.” Jim Strick, a board member and professor in Franklin & Marshall College’s Program in Science, Technology and Society, towered in front of us wearing a white t-shirt emblazoned with Reich’s famous “It CAN Be Done” quotation, demonstrating how close he’d let Will get to him before he felt his personal space being violated. Next, participants danced across the basketball court with balloons while orchestral music played—slightly odd, but a far cry from the screaming and writhing featured in footage of group therapy Serbian filmmaker Dušan Makavejev presented in his Reich-inspired 1970 surrealist film, W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism.

Psychotherapist, orgonomist, and trainer, Peter Moore spoke about how, as a cis-white male therapist practicing Reichian techniques, he has to be careful—the sounds that sometimes emerge during traditional orgone therapy sessions—sobs, moans, and heavy breathing—are dangerous sounds to be coming from a therapist’s office. Reich believed that a four-beat formula of tension, charge, discharge, and relaxation could be observed throughout the natural world, in therapy, and cells in his laboratory. He proposed a shift away from Cartesian duality toward treating the body and mind as one. Reich argued that the systems we live in—economic, interpersonal, sexual, religious, education, and political systems—impact our well-being.5 One aspect of traditional orgone therapy is the process of locating energetic blocks within a patient’s body and physically manipulating it—sometimes, quite aggressively—to encourage its release.6

Patricia Estrada, a board member, therapist, and head of the renowned Centre Reichano de Mexico shared that, in her experience, the same ends could be met with a much gentler approach and that therapists tend to resort to more aggressive approaches when they’re not able to be patient. This resonated with a somatic therapist from Vermont, who noted she would never feel comfortable using the more aggressive approaches with her patients, particularly those who had experienced trauma. A nod of understanding moved through the crowd.

In his last will and testament, copies of which the museum used to sell copies for $2, Reich declared, “To my mind the foremost task to be fulfilled was to safeguard the truth about my life and work against distortion and slander after my death.” His concern extended beyond his troubles with federal authorities. He had local problems as well.

After setting up shop in Rangeley, few of Reich’s attempts to engage the townspeople were particularly successful. Local historian Gary Priest, who lived across the street from the Reich family in the fifties said some locals thought Reich was a Nazi. “They didn’t understand what he was doing. They thought he was a crackpot. You didn’t have the media that you have today back then. Word would get around by mouth. I don’t think he had a lot of actual contact with most of the people in Rangeley.”

On the night Eisenhauer was elected, an angry mob showed up at the family’s home, yelling “Down with the commies! Down with the orgies!”7 But Reich—a Jew by birth with Marxist tendencies—had been kicked out of the communist party long ago. He fled Norway in 1939, on the last ship out before WWII broke out, living and teaching in New York City for a spell. An FBI informant noted the existence of a portrait of Stalin hanging on the wall of his Forest Hills home. (It was a portrait of Freud.) Eventually, Reich settled in Rangeley and got to work building Orgonon—a permanent home for his work.

When Kathy Steward, daughter of Orgonon’s original caretaker, reported being taunted and shunned at school because of her family’s association with Orgonon, Reich suggested she invite her class over to learn how the cloudbuster worked. People in town were under the impression that the telescope on the roof of the observatory was a machine gun and were skeptical of the cloudbusters seen on the back of trucks headed to and from Orgonon. His son, Peter, was shot at while waiting for the school bus.

Kathy, who worked as a guide at the museum for many years, told me that if a visitor seemed especially interested in cloudbusting, they might have gotten handed a faded handout titled, “Rules to Follow in Cloud Engineering.”8

Rule #1 of cloud engineering is: “Shed all ambition to impress anyone.”

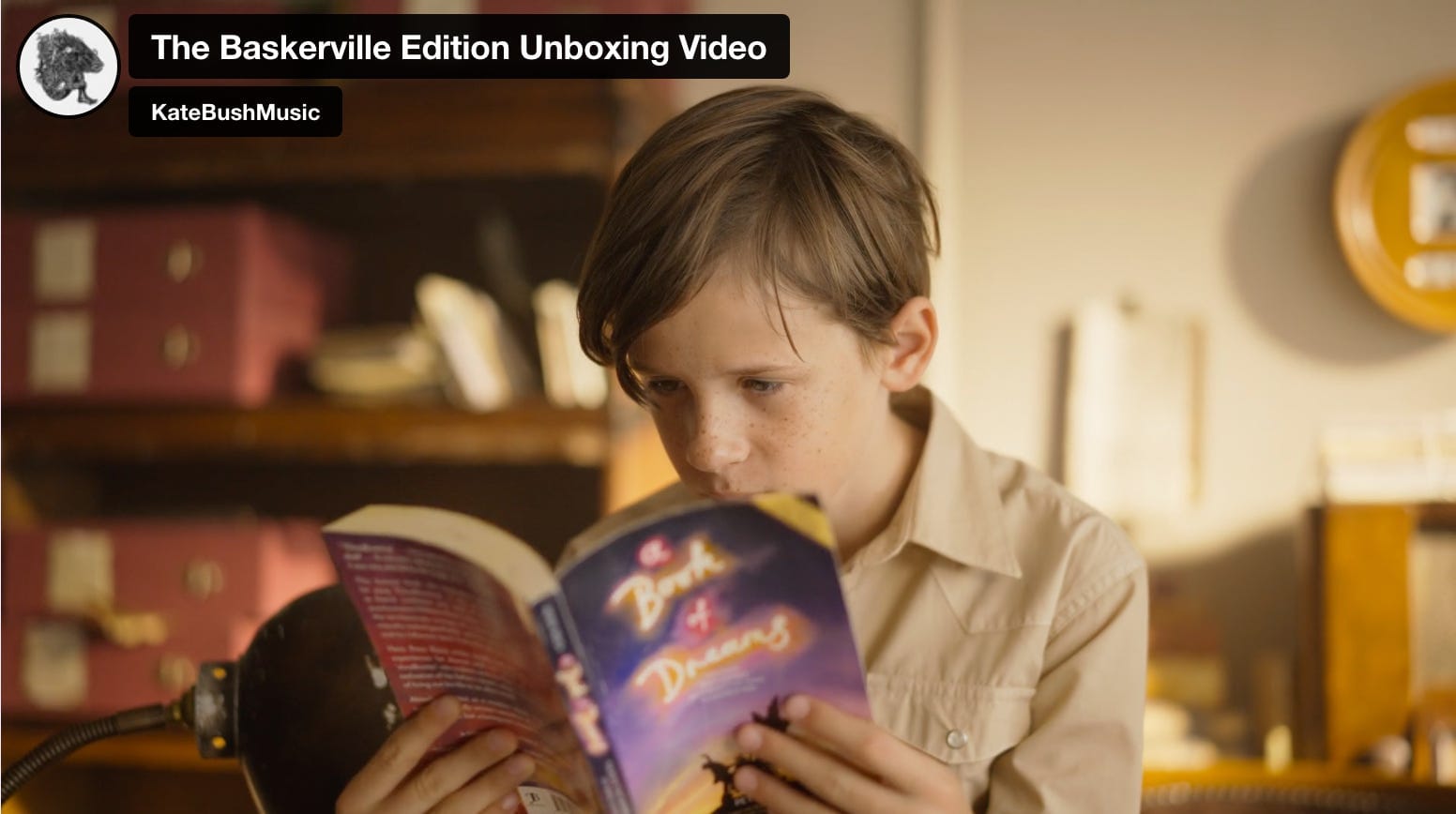

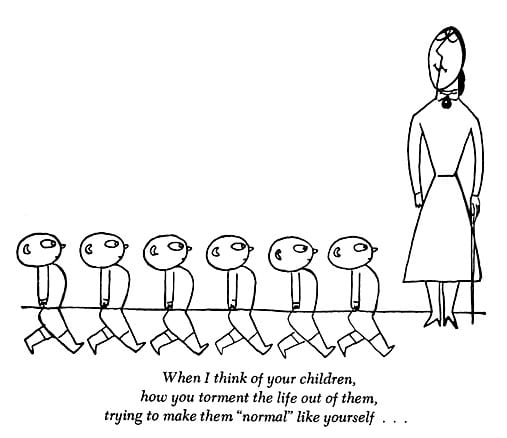

The juxtaposition of this poetic language, the cloudbuster in the corner, and the sheer beauty of the International Style building and its fraught history is mesmerizing. The museum sits on a hill overlooking a blueberry field with distant mountains all around and Dodge Pond below. What may or may not be Beethoven’s death mask hangs next to the fieldstone fireplace. An “African walking stick” given to Reich by Polish-British anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski hangs on the wall next to the treatment room. The furniture is Scandinavian. The eight ball glasses are engraved with cartoons by William Steig—a friend of Reich’s who did the illustrations for his rant, Listen Little Man! The walls are strewn with Reich’s rudimentary oil paintings, a hobby he took up in the last decade of his life. A black-and-white checkered flannel shirt hangs in the closet beside Reich’s lab coat and the wool suit he’s wearing in the formal portrait of him that hangs in the library where a mouse occasionally knocks books off the shelves; a copy of Karl Kraus’ satirical journal Die Fackel fell on the floor the day I was there. The red Armstrong Linoleum floor in the lab is the same as it was when it was full of Reich and his students and will be familiar to anyone who’s read Reich’s son Peter’s beautiful lyric memoir, "A Book of Dreams.9

Towards the end of the week, participants gathered at what is now the conference building at Orgonon for a celebration of Philip Bennett’s new book From Communism to Work Democracy: The Social and Political Life of Wilhelm Reich. Wine and pizza (“orgone pizza with a sprinkle of bions,” someone joked) were served in the building that was constructed in 1945 as a laboratory for students and now houses office, workshop, and storage space, as well as an orgone accumulator room.

Philip, 82, labored over the book’s 590 pages for fifteen years and was chuffed that it would be published though was initially somewhat trepidatious about it being acquired by such a leftist series (Haymarket’s Historical Materialism via a partnership with Brill).

“But, I suppose my heart, and my politics, are on the left,” Philip admitted.

“Can I put that on my dating profile?” a therapist called out.

Nick Lyons, an improvising alto saxophonist and composer with a Reichian therapist, took his saxophone to the lawn, serenading fellow conference attendees who took off their shoes to dance on the grass, securing themselves a fixed location in my brain as Matisse’s dancers, the sun setting behind them.

On my final night at Orgonon, I headed back over to the conference building to take a turn in an orgone energy accumulator. Sarah’s hair was wet from a shower and she’d changed from her museum guide clothing into a Mount Holyoke sweatshirt and striped cotton boxers. She showed me the paper pulp she’d been making from Orgonon flora: sweet vernalgrass from the field behind Reich’s tomb, goldenrod from the outskirts of the blueberry field, and lupines from next to the museum. Peter Reich recently remarked to me that lupines never used to grow there—even the flora has changed since Wilhelm Reich first came to Rangeley.

I placed my keys and phone on the mantle above the fireplace next to the prominent painting of Reich and entered the orgone room. Over fireside gin and tonics in the backyard of the waterfront cottage where Reich and his family once lived, Jim warned me that people don’t tend to feel (or see) anything the first time they sit in an orgone energy accumulator, and as a result, think it’s nonsense. But for a great many people, those who sit in them regularly over time can feel the effect much more clearly. However, since the room itself was an orgone energy accumulator and I’d be sitting in an orgone accumulator box inside it, I might be more likely to feel something. I closed my eyes.

I recalled the voices of panelists I’d heard during the week, eighty-year-old Dr. Lewis10 repeating the comforting lines he’d heard from Dr. Sobey, who’d heard them from Reich himself: “That’s it, let it come, let it come through, I’m here to be with you as you contact and release it.” Norwegian therapist Per Johan Isdahl imploring therapists to put aside their revulsion and judgment of patients who self-harm. I thought of Will locating a block of tension in Jim’s body, getting his consent, and then working on the spot until Jim’s shoulders fell back down, the balloons they’d danced with across the basketball court now scattered on the ground around them.

A few evenings earlier, I’d driven out to the scenic outlook above what’s now called Rangeley Lake. The sun was setting and the sky was hazy with smoke from distant wildfires. A smoking woman was parked next to me, talking into her phone about her shitty job, getting into a fight with her man, her driving off in a huff. Her cigarette smoke joined the sky—the same sky that inspired Reich to choose Rangeley as the site for his legacy.

In Everybody: A Book About Freedom, Olivia Laing writes that as Reich “…was drawn further into socialist and communist politics, he came to believe that unhealthy social conditions were producing neurosis on a mass scale and that prevention via social reforms would be far more effective than individual therapy for people already damaged.” Though Reich’s services as a therapist are part of what funded Orgonon, he also criticized therapists who were content to continue making a living treating issues they knew were caused by social ills.

It was quiet in the accumulator. I scanned my body. I thought about the many layers of metal and wool surrounding me. Later that evening, I’d drive back across the dark mountain range to my sleeping family. I’d been worried about my youngest kid, who’d been suffering from cyclical fevers all week. I hadn’t been going to therapy because talking doesn’t seem to be enough. There are no Reichian therapists in Maine, although a beloved friend keeps pushing me to go see a somatic experiencing therapist she recommends. The same friend—a radical feminist—once told me Reich tried to bottle and study a gas he believed hysterical women gave off when they climaxed.11 The friend who was excited for me to come and meet the weirdos at the conference is an avid reader of Resmaa Menakem and a student of somatics, a field of therapy for which internet searches are at an all-time high.12

Having monitored the Zoom chats of some of the Reich museum’s public offerings, I’ve witnessed the orgone-obsessed go off the deep end speculating about orgone accumulation in tipis and pyramids. I’ve heard about the ex-boyfriends who build their own orgone energy accumulators and the guy at the bar who won’t shut up about Reich. A new tattoo artist friend recently asked what I was working on. When I said Reich, they asked in a conspiratorial tone while poking their needle into my skin, “So what do you think? Was he murdered by the government?” That conspiracy theories, cloudbusting, and “orgasm accumulators”—followed by snickering—are the most well-known entry points, or barricades, to Reich’s more extensive teachings is tragic. And perhaps that’s why the guy at the bar can’t stop talking about him. Perhaps that’s why I can’t stop talking about him.

Reich advocated for sex education, birth control, the right of children, the right to divorce and the legalization of abortion, as well as practical, substantial support for mothers and families. He wrote about the repercussions of fascists suppressing sexuality and relegating sex to procreation. He wrote about the patriarchal family structure as a breeding ground for fascism, what he called, “the factory for producing obedient citizens.” Jim, who frequently assigns The Mass Psychology of Fascism to his students, says they come into class the next day after reading it asking, “Wait, when was this written? Is he talking about now?” (It was written in 1933 during the rise of the Nazi party.)

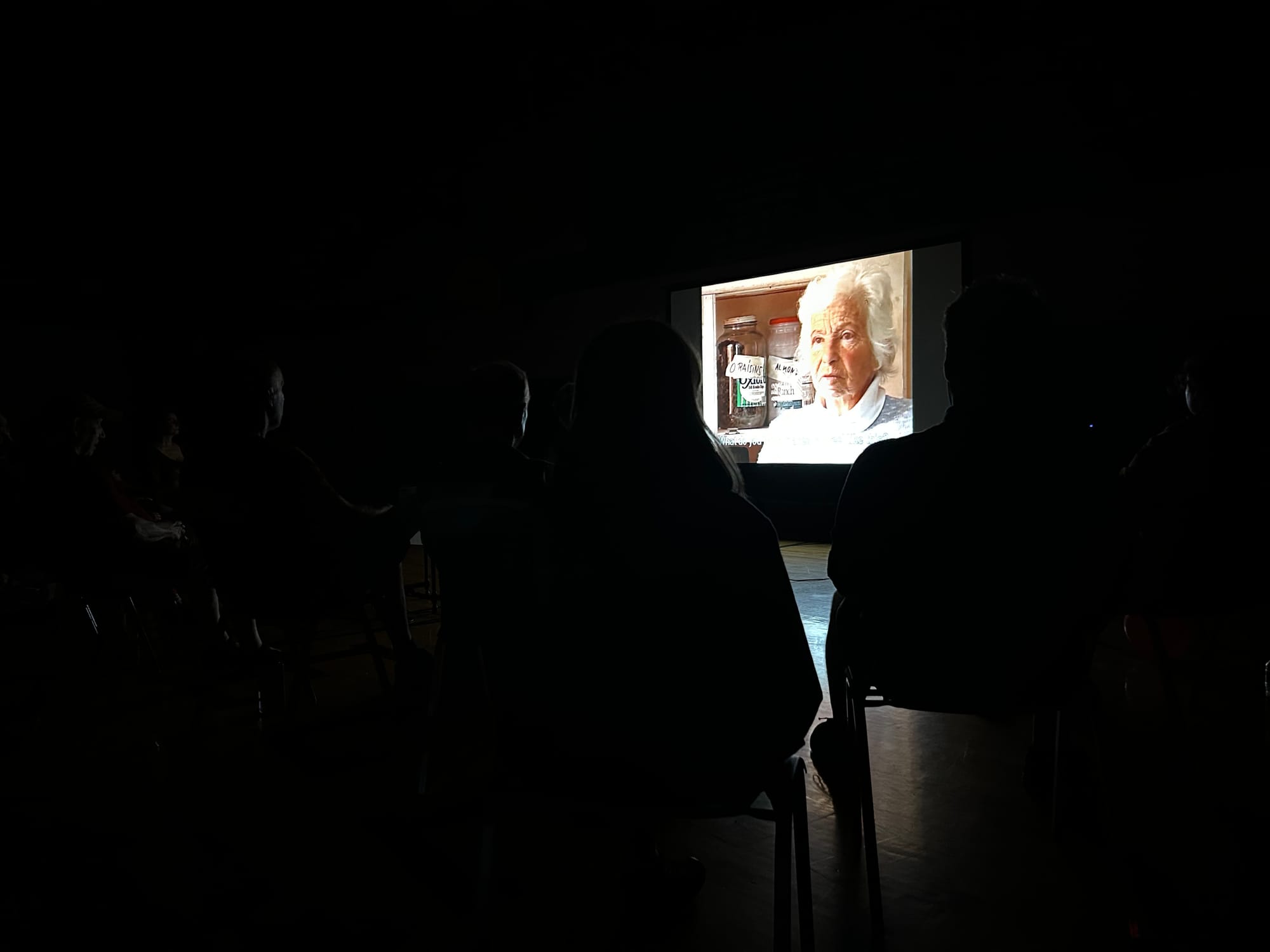

Prescient and visionary as he was, Reich was not uncomplicated. The pleasure of being among Reich enthusiasts is their collective ability to integrate his complexities. They can discuss how Reich’s work influences theirs while taking in a poignant documentary, “I’m a Doctor on an Expedition” by German filmmaker Heidrun Mössner, about Reich’s daughter, Eva Reich, who worked closely with him and spoke frankly of their fraught relationship.

I thought of the audio Wilhelm Reich recorded in 1952 after an experiment went terribly wrong. A toxic interaction between radioactivity and concentrated orgone energy fields in the accumulator room where I was currently sitting13 had caused everyone involved to get very sick, and for all the mice to die. In the recording, Reich states, “I would like only to mention the fact that there is nobody around, there is not a single soul either here at Orgonon or down in New York who would fully and really from the bottom of his existence understand what I'm doing, and be with me in what I'm doing... There is no soul far and wide to talk to, to give one's feelings - to let one's feelings go freely, to speak like - as friends speak to each other.”

I had the sense, from talking to the Reich enthusiasts who have returned to Orgonon every summer since the conferences first began in 1980 that they felt as though perhaps the laughter, love, and connection generated through these reunions could somehow lift the heavy veil that surrounded Reich and Orgonon after Reich’s death.

“There’s so much critical text on Reich, so much of a cultural shadow on him. Let’s have a little fun. Let’s celebrate him a little bit,” said Sarah.

Countless books have been written about Reich—by family members, scholars, and cultural critics. According to David, a new biography of Reich by Håvard Nilsen—You Must Not Sleep—is causing a small sensation in Norway. Yet every book about Reich contains the fact that he died in prison. And each time I come to that dreadful moment, I wish it turned out differently.

On April 22, 1957, Reich wrote to the staff of the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg where he was imprisoned, saying “I like to play piano and organ. I would appreciate information on how to obtain the opportunity to enjoy this hobby of mine.” He hoped they might grant him “an interview on this matter.”

Heart failure was Reich’s official cause of death. In her epilogue to a selection of Reich’s letters and journals, a former trustee of Reich’s estate made note of the words of a small child visiting the museum who found another way to say it: “‘I think he died of a broken heart.’”

Reich will never sit at an organ again but if you go to Orgonon, you can listen to a recording of him playing his new Wurlitzer organ. It’s the first exhibit to your left when you enter the museum. I asked David, who created the exhibit, if it would be accurate to say he’d edited out the parts where Reich slipped up. He rejected this. Reich hadn’t intended to record a polished musical piece; David had simply strung together what he considered the most representational excerpts. Whether this curatorial process is regarded as additive or subtractive, what’s left is listening to.

Here’s where you get to listen to Wilhelm Reich playing his new Wurlitzer organ:

Thank you to the Wilhelm Reich Museum, Philip Bennett, Sarah Chait, Alison Glick, Renata Reich Moise, Gary Priest, Peter Reich, David Silver, Kathy Steward, and James Strick. Thank you Heather Christle and Holli Cederholm for editorial assistance in this essay’s early phases. Thank you to the magazine editor who initially said he was interested in this piece, which gave me the courage to attend the conference in the first place. Thank you to Travis Ferland14 and the Rangeley Inn. Thank you, Cara Oleksyk for the open call to visit Orgonon with you. And thank you, subscribers, champions, and cheerers-on, especially Derek Yorks.

Check out Sarah Chait, the artist (and Orgonon resident-intern) who generously shared her illustrations with me for this piece, on Instagram (@chaitertot).

I attended the conference with the intention of writing about it for a well-resourced magazine that would pay me enough money to counterbalance the money I’ve sunk into research and multiple self-financed reporting trips to Orgonon over the past year. This did not transpire. This is why this essay is here and not somewhere else. Thank you for your support. ↩

After my first visit to the Wilhelm Reich Museum in October 2022, I visited their website and was surprised to see Renata’s face there. I don’t know Renata well, but before I knew anything about Reich, she was part of the team of midwives who supported me through my first pregnancy. Renata’s mother, Eva Reich, worked closely with Reich, and was a country doctor who established a mobile birth control clinic in rural Maine and went on to lecture on orgonomy, gentle birth, breast-feeding, sexuality, organic foods, baby massage, and run therapeutic workshops all around the world. ↩

Orgone energy, at its most simple, is life energy. It’s “Primordial Cosmic Energy; universally present and demonstrable visually, thermically, electroscopically, and by means of Geiger-Mueller counters” (of which many could be found for sale years after Reich’s death at yard sales across Rangeley). ↩

I am still trying to understand Reich’s concept of the Emotional Plague but I will say this: everyone has it in them as a result of having so many of our fundamental, biological needs denied and repressed since birth. It can provoke virulent, destructive, and savage rage and frustration when a mirror is held up for us to see how miserable we are, or when we witness freedom in another body. ↩

Reich’s emphasis on politics and sexual functioning is part of what led to his falling out with Freud—not a trifling manner, by any means. ↩

Jim Strick made me say that these techniques should only be used by trained practitioners who have a solid sense of functional anatomy, i.e., do not try this at home. ↩

“Orgies” with a hard “g” not a soft one—referring to people who believed in orgone energy. ↩

Reader, I received this handout. It wasn’t cloudbusting that got me, it was everything. My first visit was a private tour and cloudbusting was not the only thing I asked about by any means. ↩

Anyone, you know, like me or Sarah or Patti Smith, whose song, Birdland was inspired by it, or Kate Bush, whose hit song Cloudbusting is based on it, or John Lennon, who wrote one of the original blurbs. ↩

Dr. Lewis had reportedly (and understandably) been recruiting apprentices to pass on his Reichian/orgone training to younger generations throughout the conference. ↩

I trust it’s clear that this is patently false—and it’s not her fault that she was under this impression. Misinformation about Reich is rampant. ↩

Wilhelm Reich is regarded by many as the “father” of body-psychotherapy, including somatics. ↩

The room was dissasembled after the Oranur Experiment—all radioactive material was eradicated from the premises—and rebuilt in later years. ↩

Halfway into a conversation about the history of Rangeley and tourism last April, Travis and I realized that we knew each other—or at least of each other—in the late 90s. “Your sister was in my French class!” he exclaimed. ↩

Member discussion